Painting in November

Painting in November

- Russell Morton

Share this :

“A slow, tepid observation of the mundane can turn a shadow into a painting.”

In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

Rainer Sarnet’s November (2017) is a fantastically absurd, romantic drama, beautifully photographed on a silvery canvas. The film wanders through an enchanted European forest where monsters, ghosts and demons roam freely amongst the town’s villagers.

November opens with a wolf frolicking in snow. The image is washed out of contrast and the snowy white landscape is blindingly white. The sequence then cuts to a woman asleep in a room. Now, the quality of the image switches to higher contrast with bright highlights streaming through the window and deep, inky, black shadows – some may agree that this is a more conventionally lit image versus the scene prior with the wolf. Thus, through montage, we are invited to assume that the woman is dreaming of the wolf and dreams are depicted in a bright, blinding aesthetic.

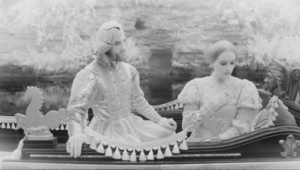

With colour films, the filmmaker may use colour theory as a device to evoke emotion, tell the time of day or foreshadow an inciting incident. Warmer tones can mean early morning sunshine or the sun setting for the day. It can evoke love or nostalgia. Cooler tones on the other hand can feel clinical, sterile or mundane. These rules are by no means gospel, however, it can be a powerful tool to evoke emotion on a subconscious level. With black and white films however, the tools available are only within the variables of contrast levels and the tonality between black and white points. November traverses between dreams and reality several times in the film and the filmmaker separates these two realms by defining them with contrast and tonal levels. Within dreams, the contrast is lighter with some areas inverted. In a scene where a kratt recalls a story of two lovers on a gondola, we see that the image is familiar but there is a distortion of reality. Leaves are white as opposed to dark grey and vignetting is inverted with a light, white feathering at the edge of the frame.

The dreams in November were in fact filmed using an infrared camera. This would allow a specific spectrum of light to reach the sensor causing strange and unpredictable shifts in colour and contrast. The result can be quite jarring and spectacular on colour images but when converted to black and white, the result is a more subtle sensation. It’s a clever approach to working within the limitations of your medium.

Despite its monochromatic palette, one cannot deny the painterly aesthetics of November. Perhaps it is precisely the lack of colour that filters the image to its very essence. Chiaroscuro light rays stream through windows, highlighting our subject and casting everything else into dust and shadows. Portraits mimic the iconic Rembrandt patch. When the Baroness sleeps, she evokes the painterly pose of a thousand sleeping women, notably Henry Fuseli’s “The Nightmare” (1781). The era of the renaissance and the Catholic imagination casts a long shadow over November. And it’s glorious. Paintings literally adorn the textured walls of the Baron’s mansion and one that particularly stood out to me was Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Judith Slaying Holofernes” (c. 1612-13) which hung in the back of the dining hall. The painting adapts the chiaroscuro style with high contrast lighting and illustrates the power of women – a central theme of the film and serves as both a literal and figurative backdrop for November’s exploration of power and servitude.

At times, I wish the process of filmmaking had the immediacy of painting, where the fleeting sensation of love and pain could be transferred immediately upon the canvas. From thought to brush stroke. Filmmaking, by contrast, requires planning, capital and bureaucratic approval. That painful sensation you had while penning the script has dulled and faded away. You can only call upon that moment by digging into the recesses of your memory, now rotting away under newer memories and emotions. Is there a more perfect form of image making than painting? Perhaps not. It is the image of the soul. It is pure imagination. Ironically, filmmakers often reference the victim of the medium they wield – that is to say that we consider the dawn of photography as the death of painting, and cinema essentially being an illusion of movement in the form of a still image flickering at 24 frames per second. But it becomes even more complicated if we consider that the battle artists are currently embroiled in is how AI has been referencing human artists, both living and dead, to create original images of their own.

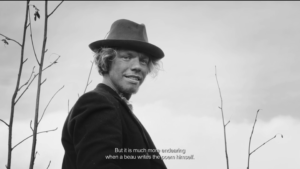

And who does the painter reference? Gentileschi, after all, was inspired by Caravaggio. Is it unfair then to demonise the machine for referencing humans – but it’s considered as flattery when a human references another human? Just like the snow kratt, whose poetry was so beautiful that it moved Hans to tears, is explained as his existence as water flowing through the rivers and fountains of humanity’s existence and by doing so, observed love and beauty through the ages. The kratt’s poetry was so beautiful that Han yearns to recite it to the baroness verbatim. The kratt says, “You can do that. But it is much more endearing when a beau writes the poem himself.” Just as the kratt was so moved and inspired by humans and their love, only then does he have the ability to tell poems by itself. And just as Hans has heard the poem that has moved him so, only then does he yearn to recite a poem for his beloved. And just as artists make great art of their own, they must first experience art so moving that it spurs their desire to do so.

But is the immediacy found in painting – the very immediacy that AI generated images also promises – so vital in filmmaking? I’d like to think not. In fact it is this very slow, stretched out process that crowns cinema its excellence over all mediums. The process of collaboration between masters of their own department begets new windows of opportunities that the solo artist would have been blinded to. Mistakes and happenstance through limitations and circumstance forces the filmmaker to come up with creative solutions. This problem solving, collaboration and world building is where we find the greatest joy in filmmaking and therefore I see little threat AI generated images can have towards the filmmaker as the very process is exactly what it is trying to take away. Just as the introduction of photography pushed painting to transcend the formal demands of naturalism and evolve into abstraction and other forms, so will filmmaking. Abstraction offers mirrors where we project our own experiences, thoughts, and emotions to fill in the gaps. Perhaps this is a bigger truth than the strive for authenticity.

About the Author

Russell Morton is a Singaporean artist and filmmaker whose work mobilises Southeast Asian folkloric figures and esoteric rituals, enmeshing mythological narratives and existentialist concerns. His short films have travelled to Fantasia Film Festival, Singapore International Film Festival, Sheffield Doc Fest, Aesthetica Film Festival.

As Cinematographer, he is credited in Kenneth Dagatan’s In My Mother’s Skin (2023), Jow Zhi Wei’s Tomorrow Is A Long Time (2023) and Petersen Vargas’ Some Nights I Feel Like Walking (2024). Morton is currently developing his first feature film project, Penumbra.

Share this :